Last updated on March 22, 2025

Mark Chapter 8, a sermon for the Outpatient Monks Birthday

Welcome again, everyone. My name is Tony. I am a theology professor here at SSW, and am now beginning my third decade as Doug Harrison’s friend. This is the part of worship service in which a short sermon or homily helps us get from the readings we’ve just heard to the bread and wine that Fr. Eric is about to invite to receive. A sermon, in the oldest traditions of Christianity, is a bridge from Word to Table. I’ll try to build us a stable bridge without taking too much of your afternoon up with engineering.

Apparently, it bothers capuchin monkeys to see a partner receive lesser rewards than themselves. See, the creatures have a sweet tooth and prefer grapes to carrots. Studies demonstrate that if one is given a grape and then sees another getting a carrot, the first will be bothered by this and often bothered enough to give the other his or her grape. What’s more, it seems that this is not just a momentary sense of fairness, but is tied to an awareness of long-term commitment to one another: that one who is eating a carrot will one day be the one with the grape, and I will one day have the carrot. These monkeys imagine a community with a future, and then they shape the kind of economy they want to govern it: one in which members look out for one another’s needs…

A scholar working at the intersection of Christian ethics and evolutionary biology-and isn’t it good to know that those fields can intersect?- this scholar suggests that we may be seeing here the ancestry of human justice and human compassion. At some level so deep within the human heart that it preexists the human being, we want to belong to communities that look after one another, care about just distribution of resources, and we want to belong to a people who find themselves moved with compassion when they see members of their larger body in need.

So in today’s gospel, it’s a very human thing-a deeply biological thing, even simian thing-that Jesus does when he says he is moved with compassion at the sight of the hungry crowd. The Greek word is a graphic one, related to the word for bowels. It’s not quite right to say that the crowd made Jesus’ bowels move… but it is something like when we say we feel something in our guts. The word is a kind of onomatopoeia in fact, Splanchnizomai –you can hear the guts churning in there, can’t you? Doctors call one of the nerves that connects the spinal cord to the abdomen the splanchnic nerve. And that’s where Jesus feels the hunger of the crowd (just like those capuchins feel the hunger of their companions).

Jesus is behaving as the blessed creature here, the icon of us all, and I believe showing us something of what it means to live together on this Earth. We can be moved toward justice and compassion even when the powers of competitive gain tell us there’s nothing we can do. Send the crowds away; it’s beyond our ability to help. Well, yes, it is… but we could share our handful of loaves and fishes. And from the creative impulse to share a simple meal there unfolds the miracle of a gift economy. No one faints, all share, all are fed and satisfied.

This is the Christian vision of the peaceable kingdom in its simplest form. Soon after this account, though, Jesus discovers that the disciples didn’t really understand what happened with the bread. The disciples are like that.

The miracle of the seven loaves that became seven leftover baskets should have taught them that God’s economy begins from excess. It’s not that the bread was metaphorical rather than literal, but that the literal bread is also metaphorical: it’s about bread, but not just about bread.

The great miracle is that God sends nourishment that turns needy individuals into a satisfied community.

The 19th c Russian classic The Way of a Pilgrim is the account of a man who wanders around Russia with nothing but a Bible, a theology book, and a bag of bread crusts, trying to learn to pray. His simple prayer, “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me,” becomes a close friend to him. He breathes the prayer, he feels it in the rhythm of his heartbeat, and it begins to bring him comfort and joy like a friend would.

At one point he explains to one of the many people he meets along the way that “our daily bread,” that line from the Our Father, is, for him, a prayer for the renewal of his supply of bread crusts. But it’s also a prayer for his prayer itself.

His love for his little prayer has become like bread to him and so has transferred a life of solitude and hunger into a life of satisfied joy. And as he goes around accepting new bread from generous strangers, he shares with him the prayer that has become his daily bread.

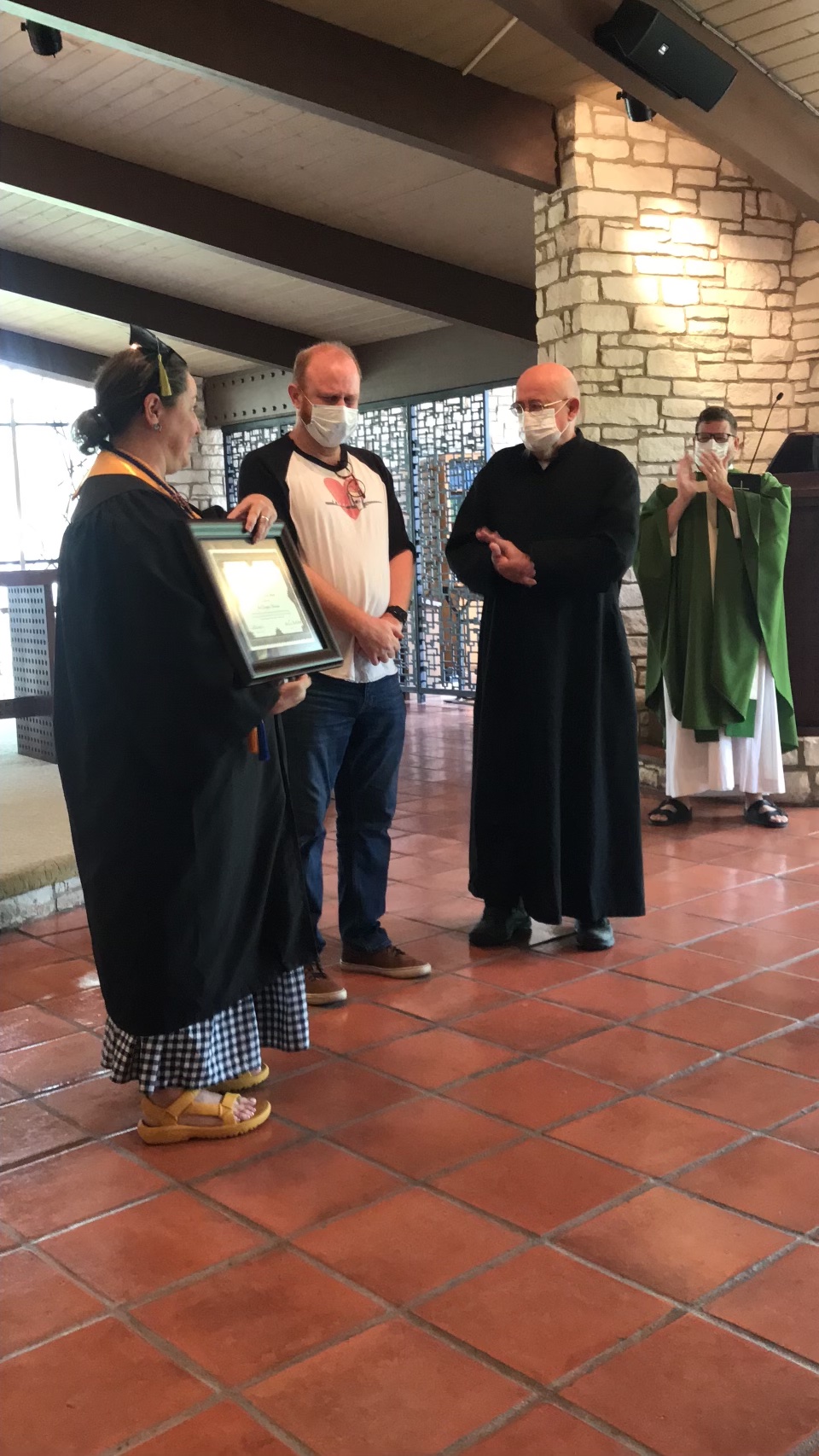

Today we are celebrating the 50th anniversary of Doug Harrison’s emergence into life in this world. And we’re doing it in this peculiar way because of who Doug is: a creature of God who cares deeply about the radical ethic of Jesus, that ethic that drives a wedge of justice and love into an economy of death and isolation.

Doug believes and trusts that in practicing a gift-giving economics, we are in fact, sanding with the grain of the cosmos, since the God who gives us our being as a gift simply is, in all eternity, an exchange of gifts.

Doug loves the miracle of baskets in Mark 8, and the simple prayer of the Russian pilgrim. And most importantly, Doug is one who wants to share the beauty and counter-cultural joy of the gospel with all of us gathered in this holy space.

You may recognize the holy number 7 that we heard about in today’s gospel-the number of loaves and baskets is the number of the day that God rested, and so the text hints that our promised satisfaction will mirror God’s ultimate satisfaction with us.

But you may be less familiar with the holy number 50. 50, in fact, is something like the number of uber-holiness. Torah instructs Israel to rest every 7th day, but then later instructs them to make a special period of resting every 7th year. And then, after every 7th, 7th year, they will proclaim Jubilee. This will not only be a year of rest but of jubilation: feasting, celebrating freedom, releasing slaves, giving to overworked land the gift of a year of growing wild.

There is some argument among the rabbis over whether this should all happen in the 49th or the 50th year, but I like to think that the ambiguous math in Leviticus is a kind of proclamation of the ultimate jubilation of workers, slaves, and fields: 50 is like the sabbath of sabbaths that knows no end. Like a theological “et cetera” that invades the multiplication table:

50 just means 49 forever. It’s the 8th day of creation. The Jubilee of all Jubilees.

So here is my proposal. Let’s make the year of Doug’s 50th birthday a year of Jubilee, anticipating the end of all things in God’s peaceable and bread-filled reign. Let’s celebrate the gift of creation; let’s be moved by the hungry child and the overworked land; let’s feel our deep humanity, our deep biological createdness down in our guts, and then let’s get creative about the ways that we can experience and share the gifts of freedom and joy and sweet grapes with one another.

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon [us,] because this Spirit has anointed [us] to bring good news to the poor.

Luke Chapter 4

The Spirit has sent [us] to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor (Jubilee).”